‘Sidney Yee: Wabi-Sai’

Thought-provoking Maui artist with 40-year ceramic and painting career honored with retrospective at Schaefer International Gallery

Contemporary realism is masterfully represented in Schaefer International Gallery’s exhibit, “Sidney Yee: Wabi-Sabi,” currently on display until Sunday, June 2.

“For me, as curator of this exhibition, Sid’s community involvement was what was so appealing to me in developing this retrospective,” notes Neida Bangerter, director of Schaefer International Gallery. “Aside from his enormous talent, Sid’s distinction is how much he’s given back — after teaching for 35 years, he still teaches at Kaunoa Senior Center [in Paia].

“He’s also done a lot for the MACC over the years; he used to come paint my walls for exhibits.”

This impressive exhibit entices the viewer to take their time strolling through 40 years of Maui educator Yee’s artistic career. Allotting oneself time to quietly contemplate the depths of Yee’s work is advised. The design of the exhibit is moody and low lit. Observed from a distance, many pieces appear simple in composition. It is on closer scrutiny that their intricacy is revealed.

Upon entering the gallery doors, turn left to follow the natural chronological progression of Yee’s work beginning with an untitled ceramic piece created in 1975. Resembling the shape of traditional Japanese kokeshi dolls, it is on loan for the exhibit from the Hawaii State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, Art in Public Places Collection. Visitors will notice tables placed centrally in several rooms holding examples of Yee’s ceramic works — many non-utilitarian sculptural shapes formed on a potter’s wheel.

Yee gravitated to ceramics in college, preferring to work in the three-dimensional form of clay, liking how the hard finished piece was so different from the soft beginning.

He focused entirely on ceramics until 1995 when he returned to school during a sabbatical leave from Lahainaluna, and he began taking painting classes at University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Yee’s paintings adorn the wall spaces of the gallery, beginning with one of his first, “My Brother Rodney’s Family.”

Painted in 2002, this large-scale painting depicts his older brother Rodney with his family. It’s a dynamic picture — one can easily “hear” the laughter and bantering conversation, you can “smell” the enticing aromas of the food crowding the table, as well as sense the love and affection the subjects have for each other.

Anyone raising a teenager will also recognize the body posturings of Rodney’s daughter as she respectfully tries to interject her opinion.

“We used to get together every Sunday and have a family dinner,” explains Yee. “[This painting] had to do with raising a kid, and having expectations for that child to grow up respecting family values, and learning to be a good person, and the daughter is raising her hand like, ‘Wait a minute, don’t I have a say in this?’

“I created a separation between the red side of the parents and the blue side of the daughter in a warm, bantering setting. Nothing serious about it.”

Yee was just beginning to paint when he decided on this project, and everything about this piece was a learning experience for him. He wasn’t even sure he could pull it off — he recognized the difficulty in representing people’s faces and felt he was showing “more guts than brains” with this undertaking.

“I used this big format to make people when I didn’t even know my ability in drawing people.

“I never told him I painted a picture of him, so when [Rodney] came to the exhibit, he dropped his jaw,” chuckles Yee. “He stood next to the painting, and everybody was taking his picture.”

There is an almost sculptural aspect to Yee’s paintings. Ever the multi-dimensional artist, Yee uses material like paper, fabric and magazine cutouts on his canvases. He consciously doesn’t overpaint them, preferring to leave areas untouched as to allow those substances to show through.

Yee takes his time before answering whether he is trying to tell a story or work through an emotion with his art.

“Both,” he suggests. “Some pieces have to do with my son’s passing; others are a critique on the environment — man versus nature. There are the realities as you get older — you go from things that are important to you — a car, a home, a TV set — then, as you get older, the spiritual things become more important to you.

“How you shift your spiritual reality is more important than something you have. You think about little things about the past; what your future is going to be; how you spend your days, which becomes more and more precious.

“At one point, I figured out if I painted things that I was interested in at the time, those ideals should come out to be something special.”

Yee admits that, of late, his focus is on what will be fun to do. He’s looking for projects he deems worthwhile, not just what will sell, and wholeheartedly believes the more personal he can make his work, the more universal will be the appeal.

Bangerter acknowledges that for an artist, how one approaches the blank canvas is an important consideration, and she respects Yee’s approach when beginning a new work.

She points out how much harder it is to internalize, go within your soul, face your life’s experiences and incorporate your imagination in a piece rather than just replicating what’s in front of you.

“It’s a lot harder to do something that is unknown, than to do something already seen,” she posits. “And to continually be able to do that for 30 years? People need to pay some attention to that.”

One cannot help but notice the multitude of tea bowls — both ceramic versions as well as depictions in several paintings. Yee smiles and says he just finds them interesting.

“I didn’t know very much about Japan, the aesthetics,” he admits. “I really liked the architecture of Japan. I liked the tea bowl because it was a simple form, yet carried a lot of meaning. I liked the idea of something simple being so dynamic and pretty.”

He adds that during his first visit to Japan, he bought a tea bowl. While crossing the country, he came upon the town of Mashiko, which was a hotbed for contemporary ceramics. Japanese ceramics were beginning to become popular in the West, and there were tea bowls everywhere he looked. He happened upon one shop and walked to the back where all the important works were kept. There, on a high shelf, he found a tea bowl he wanted — it was $200 for a single bowl.

“From then it became something for me. I got a job teaching in Japan in the summers, and every summer I would buy at least one tea bowl . . . then I discovered eBay,” Yee chuckles. “Then I didn’t have to buy in Japan. I believe I bought about 50 [tea bowls] from Japan.”

When this exhibition was first broached, back in 2016, Yee promised Bangerter he would make 50 tea bowls. Then he thought to himself, “Why not make 100?” Then before long he believed he could tackle making 200 expressly for this show.

“And he did,” laughs Bangerter. “Everbody’s loving them.”

Yee becomes serious as he admits making the tea bowls is still mystery to him.

“Seems something so very simple can be very complex,” he professes. “It’s a challenge that has kept me interested; something I had to struggle with.

“Just setting up a ceramics studio was a task.”

He sheepishly offers that he spent time building a structure to house a gas kiln. He then purchased hundreds of dollars of glazes, only to realize too late the glazes were for an electric kiln. He mentions how the craft of ceramics has changed from when he worked with them years earlier.

“I think the tea bowl is symbolic to wabi-sabi and an important implement in the tea ceremony,” explains Yee. “Everything seems to be connected. The making of these 200 tea bowls allowed accessibility to my work because people can buy [a bowl] — it’s not that expensive — and they can be a part of the whole wabi-sabi movement.”

Wabi-sabi, for the uninitiated, is explained on the website www.japanology.org as “the Buddhist view of the facts of existence: Both life and art are beautiful not because they are perfect and eternal, but because they are imperfect and fleeting. . . . Whereas classical Western aesthetic ideals were of beauty and perfection, of symmetry and a fine finish, wabi-sabi is hard-nosed and realistic: Nothing lasts, nothing is perfect.”

The exhibit piece, “Walls and Doors,” exemplifies the wabi-sabi aesthetic that small things are as beautiful as something large.

“I use the metaphor of a goldfish a lot because it represents temporary beauty.

“The goldfish is raised for beauty, not for longevity. They’re kind of a chunky fish. They’re round. A hearty fish is long. So their [goldfish] shape causes them not to last very long,” he explains.

“The point is you must enjoy the moment, because it’s not going to be like that forever. I use the goldfish in the painting to show the beauty is in the small things.”

Yee has been on an interesting life’s journey. Born on Oahu, where he was raised in Waipahu, he dreamed of settling down on a Neighbor Island. He harbored a romantic notion that the slower-paced outer islands would suit his personality.

Attending University of Hawaii at Manoa, Yee received both his undergraduate and Master’s degrees in art education in the 1970s. He taught art at Leilehua High School in Wahiawa on Oahu.

Yee’s Neighbor Island dream became a reality in 1975 when a position to teach art opened up at Maui High School. After five years at the Kahului school, Yee accepted a position at Lahainaluna High School, preferring the smaller size of the school. Soon he found himself immersed in Maui’s community, settling in and raising two children, including daughter Saedene Yee-Ota, owner of award-winning Sae Design, and part-owner of the now closed, Maui Thing.

“It was so wholesome here,” marveled Yee. “It was easy to get children involved in programs.”

Yee has had a prolific career on Maui. One of his most high-profile ceramic works, “Ke Ala O Ka Mana,” is installed in the ticket lobby of Kahului Airport and welcomes visitors and residents alike to the lush beauty of Maui.

In describing his process for creating his work, Yee explains he tries to put a bit of mystery in every piece, and doesn’t believe his work neatly fits in the realistic definition often used to describe it.

“There’s a mixture of abstract with the representation of what you recognize. Sometimes it’s more abstract. I try to cover all my bases of what make a good work of art.

“I would definitely look at what colors I’m using, that I’m using colors that work well together. I use images that you wouldn’t normally put in a setting to cause the picture to be something that needs interpretation.

“Then the interpretation becomes the participation of the viewer to the painting. The process of interpreting what’s happening in the pictures is what is really memorable.”

Yee acknowledges that he often approaches a project wondering “what’s going to work.” When working on a series, his methodology is to keep working, making each piece unique, until he has exhausted all possibilities. He consciously explores territories that he hasn’t ventured to yet, experiencing things he’s unfamiliar with, hoping to create a solution that is something different than what he’s done before. His biggest disappointment would be to finish a painting and realize it had the same elements as a previous painting.

“I wanted to prove to myself that I could paint anything or paint nothing and make it something.

“I feel I have a responsibility to people who look at my work to show them something different, something new. I think by doing that, that is why I have been accepted by the state foundation many times because the foundation looks for things that are unique.”

Yee admits he never thought he’d be a teacher. He planned on becoming an architect, until he realized it would take too long to complete the studies.

Fate, perhaps, intervened in the form of a push by the state of Hawaii in recruiting male teachers — up to that time, most teachers were female, and the state saw a need to bring men into the profession. He knew he had talent as an artist, so he pursued an arts education degree.

The words of one professor really stuck with him: ”Teach to a student’s needs.”

These words helped him recognize the need to individualize his instruction to the needs of the student.

“One thing I did know for myself was that what I taught was important — art was important. Art enriches your life, it gives you thinking skills.”

In looking back over his life, Yee points to his career as an educator as that of which he feels is the most important. Helping students is what he is most proud of accomplishing. It was that sense of personal fulfillment that took him to Kaunoa Senior Center after he retired from teaching. He proudly points out he’s had students from there who have successfully entered the prestigious juried show, Art Maui.

When asked if one particular piece from “Wabi-Sabi” stood out for him, Yee thoughtfully pointed to “All My Sorrows That Tomorrow Brings Takes Me Back” from 2017. Executed in dusty shades of mauves, dark blues and browns, with even the brighter sandy colors taking on a dulled tone, it is arresting to look at and makes one feel contemplative.

“It represents my life and everybody’s life, which is a journey,” he muses. “It’s about going through the stages of growing up. I tried to capture the feeling of sometimes we look at the past too much. We look at things that are meaningful to us, but that are fleeting. There’s a yearning to have your time of youth back. It’s bittersweet. Wabi-sabi says to cherish the moment; don’t look back. All there is, is there — yet we still yearn.”

* Catherine Kenar can be reached at ckenar@mauinews.com.

_______________

“Sidney Yee: Wabi-Sabi” is currently on exhibit through June 2 at the Schaefer International Gallery at Maui Arts & Cultural Center in Kahului. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday. The gallery is also open during Castle Theater shows and during intermission. For more information, visit www.maui arts.org or call 243-4288.

- “Weaning” (2013) — Photo courtesy Maui Arts & Cultural Center

- “All My Sorrows That Tomorrow Brings Takes Me Back” (2017) — Photo courtesy Maui Arts & Cultural Center

- “Walls and Doors,” (2018) — Photo courtesy Maui Arts & Cultural Center

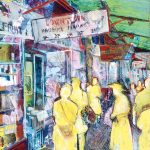

- “Tourist,” (1997) from the Chinatown series — Photo courtesy Maui Arts & Cultural Center

- “My Brother Rodney’s Family,” (2002) — Photo courtesy Maui Arts & Cultural Center

- “My Red Wheel Barrow,” (2008) — Photo courtesy Maui Arts & Cultural Center

- Examples of Sidney Yee’s earliest works — TONY NOVAK-CLIFFORD photo

- Artist Sidney Yee alongside his 1996 mixed media piece, “Chinese Ghosts, Chinese Money.” This piece is on loan for this exhibit from the Hawaii State Foundation on Culture and the Arts. — NEIDA BANGERTER photo

- Some of the tea bowls Sidney Yee made specifically for this exhibit. Many are still for sale. — Photo courtesy Maui Arts & Cultural Center

- “Half Empty or Half Full” — Photo courtesy Maui Arts & Cultural Center

- “Elements in Forming a Tea Bowl” — Photo courtesy Maui Arts & Cultural Center