Molokini, sans the snorkelers, gets in-depth look with survey

Team to observe coral reefs, sea life

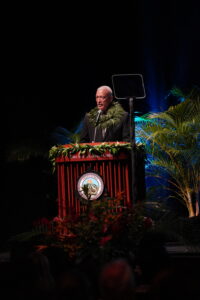

Scientist Alan Friedlander conducts fish surveys earlier last week along Molokini’s reefs. Photo courtesy of Kevin Weng

A research team last week began studying the ecosystem around Molokini — without the usual tour boats and crowds of snorkelers — to observe any changes. They already have noticed a few.

The protected Marine Life Conservation District drew more than 360,000 snorkelers and divers in 2018, according to the state Department of Land and Natural Resources, raising concerns about impacts to sea life and coral in the partially submerged crater off South Maui. Tours have stopped since COVID-19 emergency orders in late March and the collapse of the tourism industry.

Local scientists are taking the opportunity during the pause in tourism to redo scuba surveys conducted several years ago, which showed that Molokini was the most effective marine protected area in the state, as well as study the reef and species’ changes in behavior in the absence of tourism.

“Molokini Crater is one of the most dramatic natural areas in the main Hawaiian Islands and harbors coral reefs, as well as fishes, sharks, manta rays and other wildlife,” said Russell Sparks, aquatic biologist for the DLNR Division of Aquatic Resources-Maui. “Under normal conditions, tourism activity is very high at Molokini, with diving and snorkeling boats visiting continually. Now, there is no tourism.”

Sparks is leading a small team of researchers for the remainder of May and into June to conduct diver surveys of fish and other wildlife, said the Maui Nui Marine Resource Council. The research began May 19.

The team includes Kevin Weng, associate professor at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science; Whitney Goodell, National Geographic fellow and marine ecologist with the Fisheries Ecology Research Lab at the University of Hawaii; and Alan Friedlander, chief scientist of Pristine Seas and National Geographic Society and director of the Fisheries Ecology Research Lab at UH.

Friedlander is the co-author of five research publications on Molokini conducted in collaboration with the Division of Aquatic Resources.

“It is pretty early into our study, but we have observed numerous predators, like ulua, omilu and other jacks, inside the crater and several sharks on the backside, plus a few very curious bottlenose dolphins who checked us out,” Friedlander said last week.

Past observations from the Aquatic Resources Division and other local operators confirm that these species have not been seen in any abundance in Molokini “in a long while.”

The scientists will install a network of tracking receivers and tag animals with telemetry devices. Vessel activity will be counted using a time-lapse camera, which builds on previous work conducted by Friedlander’s lab in collaboration with the Aquatic Resources Division.

“Molokini is normally visited by 1,000 tourists every day and is one of the most visited marine protected areas in the world,” said Robin Newbold, co-founder and chairwoman of the Maui Nui Marine Resource Council, in a news release on the studies. “Many Maui residents are wondering what’s happening there now that the tourists are gone. We’re excited that these scientists have stepped forward to collect data relating to this important question.”

“It’s important to “examine the abundance and movement of animals now before visitors return” so that scientists can get a comparison, Friedlander added.

The amount of traffic at Molokini can hinder fish reproduction and behavior, and the overall success of the surrounding ecosystem, scientists say.

Weng said last week via email that they spotted omilu and dolphins during a recent dive at Molokini. Prior research indicated that omilu usually moves away from the crater when “there is a lot of boat and tour traffic,” he said.

Though tour boats are not around, Friedlander said Friday in a phone interview that the team has spotted fishing boats and poaching in the crater. With less tourist traffic and regulation, “some people are taking advantage of the situation,” he said.

With previous and current research, the scientists hope to bring back a proposal in the Legislature, which aimed to reduce the number of moorings at Molokini, more in line with a DLNR proposal of a dozen boats.

“Resurrecting that based on a lot of good science and a lot of good social science, and good management advice from the Division of Aquatic Resources on Maui” would help to reduce the crater’s use by tour boats and fishermen, Friedlander said.

This would still allow for economic opportunity without exhausting Molokini’s resources by finding a balance between conservation and commercialism.

Commercial operators opposed the proposed measure, saying that the number of boats was too limiting and that additional scientific studies needed to be done to prove negative impacts of boats and people. One operator said that the baseline studies for omilu are needed.

A more tour-operator-friendly measure that put a 40 operator cap on Molokini passed the state Legislature last year but was vetoed by Gov. David Ige.

According to nonprofit Maui Nui Marine Resources Council, the scientific team has permits to travel and to work at Molokini. Through the council and community donations, the researchers have “received overwhelming support,” including free lodging opportunities, a car and more than $3,200 in funding to help cover expenses, like fuel for the boat and other supplies.

To follow the research team’s journey, visit their blog at molokini.blogs.wm.edu.

For more information, email info@mauireefs.org and to make a donation to the research project go to GoFundMe at gofundme.com/f/molokini-during-covid-19-research-study.

* Dakota Grossman can be reached at dgrossman@mauinews.com.

- Scientist Alan Friedlander conducts fish surveys earlier last week along Molokini’s reefs. Photo courtesy of Kevin Weng